It's about 10.30am forty years ago – October 1, 1983 in Bathurst, NSW.

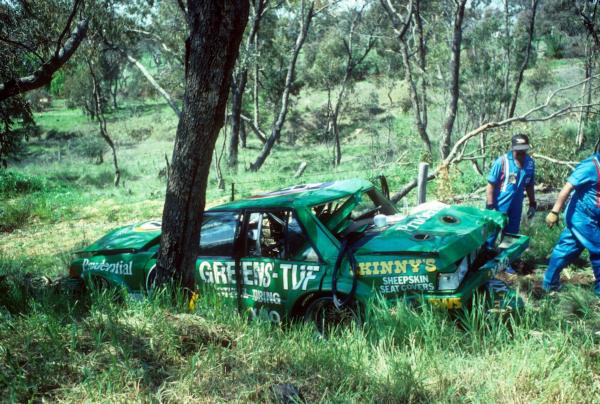

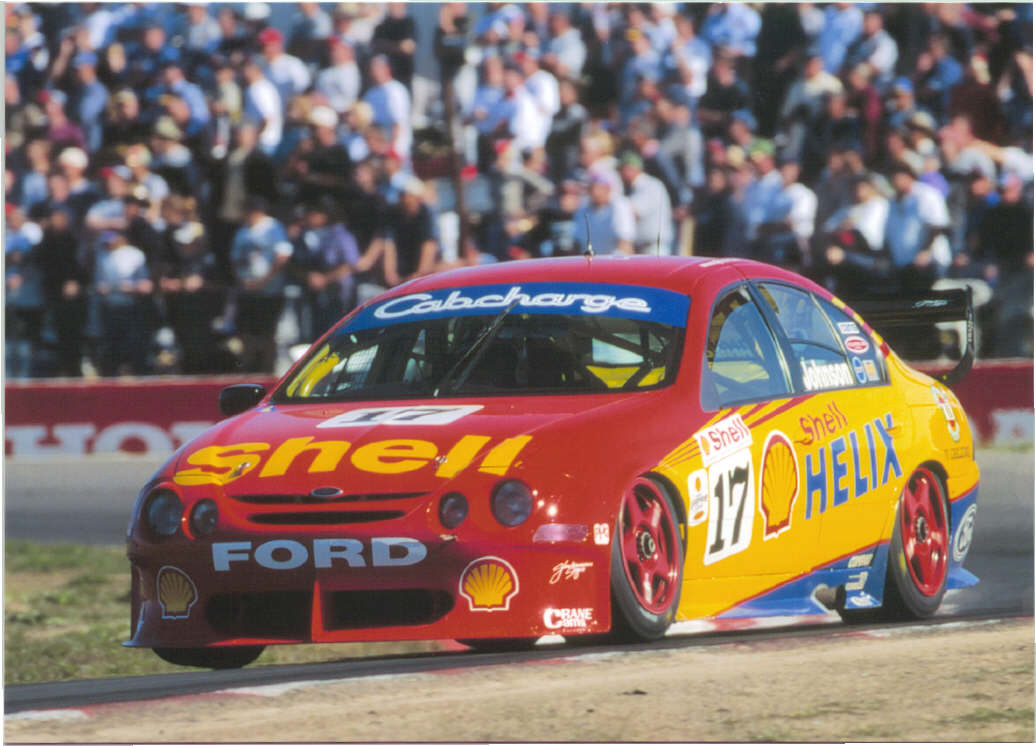

Dick Johnson, at the wheel of his iconic Greens-Tuf Palmer Tube Mills No.17 Ford XE Falcon crossed the line to start his lap in the Hardies Heroes – now the top-10 shootout – in a quest for pole for the James Hardie 1000 the next morning.

His Bathurst fortunes had been up and down over the past couple of years. He famously hit a rock rolled onto the track by a fan in 1980, and then brought a brand new car in 1981 and won it.

READ MORE: 'Justin Bieber of league' could make the game millions

READ MORE: The Gould question Freddy can't answer after quitting

READ MORE: Awkward problem caused by Warriors great's return

He finished fourth in 1982 but was disqualified after stewards in post-race scrutineering determined his team had modified the cylinder heads.

Johnson said his team later took a brand new set of cylinder heads to them in an effort to have the decision overturned. They refused.

"We just had to f--king cop it," he told Wide World of Sports a week out from the 2023 edition of the race.

He arrived at the Mountain in '83 with a new co-driver, Kevin Bartlett. They had a fast car, and Johnson felt they would go into the race favourites.

The lap

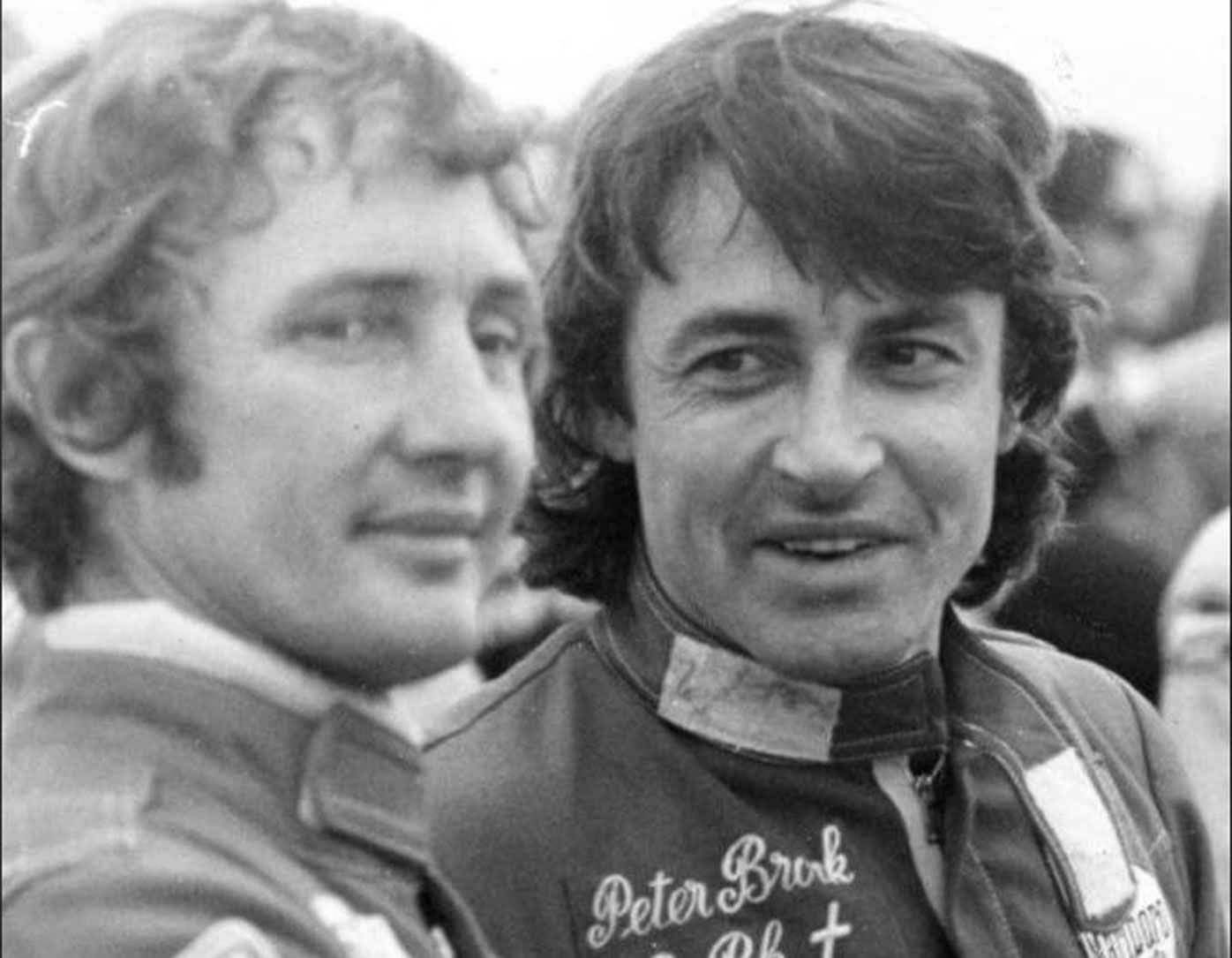

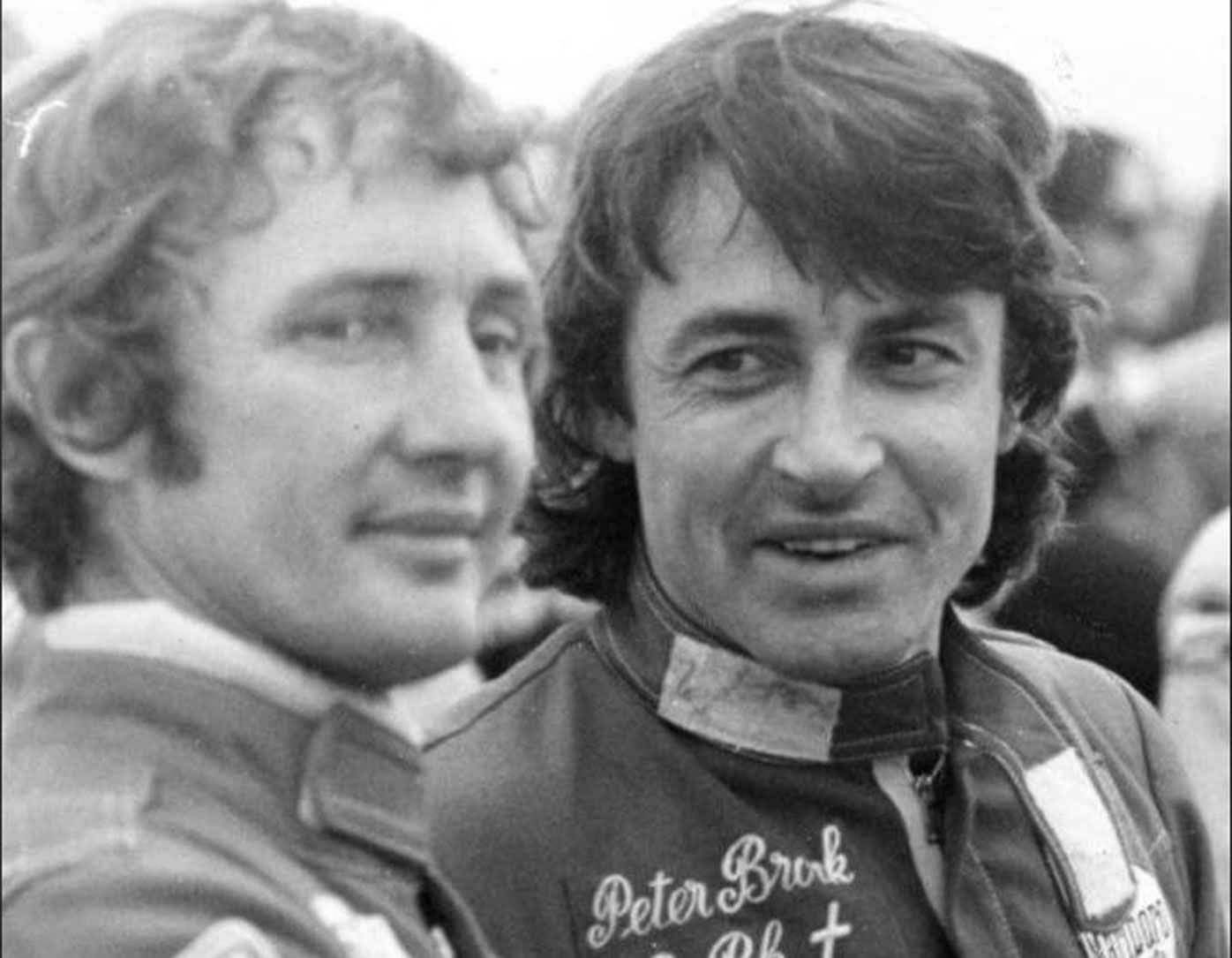

Johnson did a 2min16.3 seconds to qualify in second place, a second behind who else but Peter Brock.

Back then, the Hardies Heroes was the fastest eight cars and two wildcards, and each driver had the opportunity to do two laps in a final effort to start from pole.

The two wildcards would go out first, and then through the qualifying lineup in reverse order. Rinse and repeat.

Johnson would be ninth to set his lap.

The massive V8 slid through the first turn, called Hell Corner, and straightened up to make the charge up the long, uphill Mountain Straight.

On the exit of The Cutting, the Falcon brushed past the weeds growing out of the earth embankment. There were far fewer concrete walls then.

Through the undulating sections past McPhillamy Park and across Skyline, the car was remarkably settled.

In his book covering the '83 edition of the race, motoring journalist Phil Tuckey recalled watching the lap on a TV screen in the BMW pit.

From somewhere over his shoulder a team member could barely believe the level of commitment on display.

"Holy f--k, he is absolutely off this planet," they said.

Johnson left two massive tyre marks as he got on the power as the car compressed through the Dipper.

He nearly put two wheels in the dirt as he turned in at Forrest's Elbow – the final corner before Conrod Straight.

What happened in the next 10 seconds began one of the most iconic series of events in the history of Australian motorsport.

"It was full on, I was giving it everything I had, and used every inch of the road and some," Johnson said.

"The car was not behaving as well as it should … it had too much understeer, and when I got to Forrest's Elbow, the understeer took me towards the concrete wall."

The first half of the Elbow is positively cambered – that's to say the road slopes towards the inside of the corner. The second half, the opposite. It has negative camber, and the road slopes towards the outside.

As the massive Falcon rounded the corner and the camber-change, understeer became oversteer and the rear-end stepped out.

Johnson said he thought he would give the concrete wall a bit of a kiss, which would straighten the car up, and he would power down Conrod.

But instead, that first impact was heavier than he expected, and it lifted the car into the air slightly. As it settled, the front wheel clipped the concrete-filled tyre bundle that protected the traffic that would travel in the opposite direction for the other 51 weeks of the year from the end of the concrete wall.

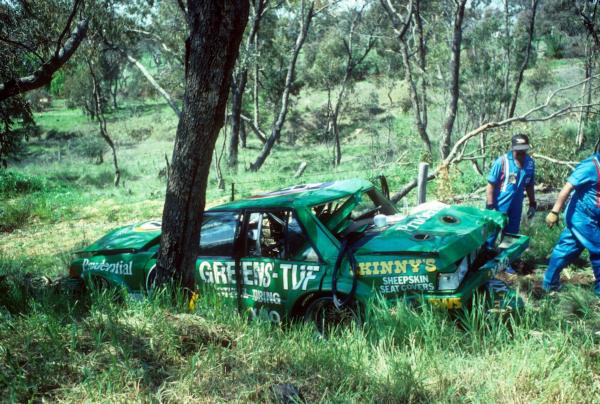

It snapped the steering arm, and when the car landed, the wheel turned hard right and fired the car straight into the bush.

Tuckey, who died in 2016, described the crash as "the sort of revenge the mountain waits for all year".

Miraculously, Johnson was alive. The car though, was most definitely not.

To complicate manners, the Falcon carried Channel Seven's world-leading Race Cam which was a far stretch from the lipstick-sized cameras that sit in the cars today.

It was a massive unit – a full-sized television camera mounted to the rollcage, with a box carrying all the other bits and pieces required to run it that weighed about 20kg mounted to the floor.

"Once I went through the trees and the car stopped, I couldn't get out of the driver's side," Johnson said

"I crawled over the camera and I can't remember a thing after that until I (was) walking up the back of the pits with Jilly."

Jilly is his devoted wife Jill. The pair have been married for more than 50 years.

When Johnson slid off the road, he took with him a television cable running along the side of the track. Screens in pit lane went black a split-second after Johnson hit the trees.

It only added to the sense of angst that was sweeping through the paddock. Jill, who usually confined herself to a corner of the pit garage, ran out the back in tears.

If you're wondering why the footage from that onboard has never seen the light of day, a Seven producer forgot to press record before Johnson left the pits.

The legend goes Johnson's co-driver, Kevin Bartlett offered to recreate the crash "for a heap of money".

The conversion

Peter Brock was on his warm-up lap before his own hot lap when he came across the crash scene. He stopped and gave him a lift back to the pits, arriving about 11am.

"And then by midday, we'd done a bit of a deal and that's when the boys got to work," Johnson said.

That "deal" was with fellow competitor Andrew Harris, who had offered to 'donate' – with a lot of money, Johnson added – his Channel Nine-sponsored Falcon to get the No.17 back in the field. The money came from Ross Palmer, of Palmer Tube Mills.

Harris recognised the punters across the top of the mountain would much rather see Johnson in the race than himself. He would later say the idea came to him after Jill ran past him as she left the DJR garage.

Although they were both XE Falcons, Johnson said the two cars were "significantly" different.

While Harris was more or less a privateer running the race on a shoestring budget, Johnson's team was one of the most professional on the grid.

Both Johnson and Bartlett did a couple of slow laps of the circuit that afternoon to make sure the car wasn't a complete death trap. They lapped some 15 seconds slower than their own car, but the deal was done.

The DJR crew got the mangled wreckage of the No.17 back some time in the mid-afternoon and then stripped it of any salvageable running gear.

Work commenced converting No.9 into No.17 about 5pm. It was an all-night job. By the time all Johnson's spares had been bolted on, dawn was approaching, and the car was sent to a crew of 10 apprentice panel beaters, painters and signwriters.

A job that would normally have taken four days, they did in four hours.

To this day, the Bathurst TAFE still plays a vital role in repairing crashed cars over the weekend of the Bathurst 1000, particularly in the support categories.

While changing cars was permitted in the rules, it would usually mean a rear-of-grid start.

In a display of incredible sportsmanship, the rest of the field voted to let Johnson start the race from 10th.

Johnson had earlier joked he planned to use the warm-up lap to dry the paint, but that was the reality. The field had well and truly formed by the time he rolled onto the grid.

But the fresh green paint was still wet – a fact learned the hard way by Seven startline reporter Evan Green, who leaned up against the side of the car, and got paint on his bright red jacket.

Johnson told Wide World of Sports a moment like that is unlikely ever to happen again – the sport is far too professional.

Perhaps the teams let Johnson start 10th because they knew he was no chance to finish.

Indeed, the car expired on lap 61 of the 163-lap journey with a flat battery – a fuse failure meant the alternator wasn't charging it.

The part cost about five cents.

It can't get any worse, can it?

Driving with Larry Perkins, Brock won the race - his seventh of the nine Bathurst titles he would eventually win.

But that wasn't without controversy either - his famous No.05 blew an engine on lap eight, so Brock and Perkins jumped into the sister No.25 car driven by Brock's brother Phil and John Harvey.

Since Harvey had started the race and turned laps in that car, he is listed with Peter and Perkins as the winner of the race.

An example of a royal shafting, Phil is not. That decision was one of a series of events that drove a wedge between the pair.

Harris meanwhile, who was forced to drive a Commodore after another replacement Falcon couldn't be sourced in time, finished 10th.

As part of the deal to use the Harris car, Johnson promised to take the car back to Queensland and respray it, and borrowed Harris' Ford F100 Towmaster to get the car back up there.

The borrowed Harris car was on the Towmaster, which was also towing a trailer carrying the mangled wreck.

More disaster. 40km out of Bathurst, the tow ball broke and the whole rig went off the road.

Johnson was once again unharmed. But the F100, the Harris car and the trailer were all destroyed.

When he eventually got home to Brisbane, his house had also been broken into.

'I'm still bloody here'

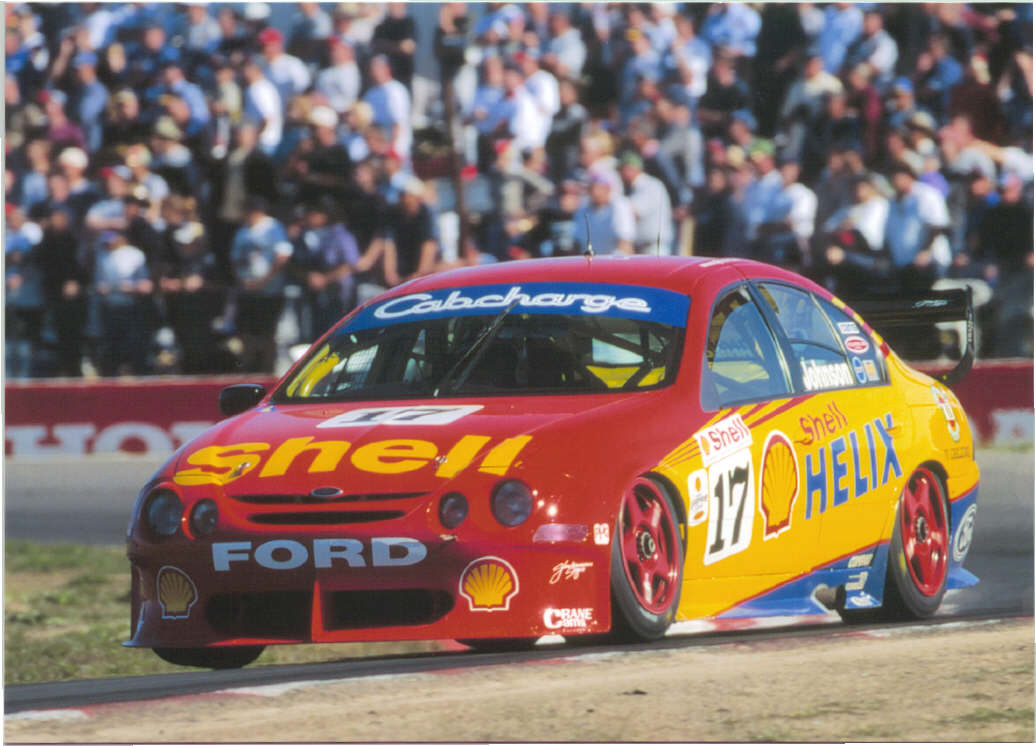

Johnson would win the race twice more, in the insane Ford Sierra RS500 in 1989, and then in a Ford EB Falcon as the five-litre formula that went on to become V8 Supercars was in its infancy.

He was driving with John Bowe on both occasions.

DJR ran the Sierras for six seasons during the Group A era. He recalled to Wide World of Sports he nearly claimed a bizarre Bathurst trilogy when he nearly hit a dog across the top.

"I thought to myself, 'jeez, that would've meant I'd hit mineral, vegetable and animal'," he said with a chuckle and all the hallmarks of a tale oft told.

He retired from racing in 1999, handing his iconic No.17 to his son Steven, who raced it until the end of the 2012 season.

These days, Johnson still runs his eponymous team with Ryan Story. The team's base is located in Stapylton, half-way between Brisbane and the Gold Coast.

"I'm still bloody here, working every day," he said.

The team last year became the first ever squad to compete in 1000 races in the Supercars/Australian Touring Car Championship, appropriately at the Bathurst 1000.

He still attends most races, and has no intention of slowing down.

It's been a difficult year for the Ford teams. The introduction of the Gen3 car has brought with it a heavy debate surrounding parity.

Of the 23 races so far, the Chevrolet Camaro has failed to cross the line first only once. Johnson's team is responsible for the only Ford win of the year, through Anton de Pasquale in the Sunday affair in Townsville in June.

Johnson has been a vocal critic of how the sport has handled the parity issue.

Alas, DJR have three cars entered for this year's Great Race.

De Pasquale and Tony D'Alberto will steer the No.11 entry, with brothers Will and Alex Davison in his iconic No.17.

But for Bathurst only, they will also run a third car — a wildcard entry for Swiss superstar Simona De Silvestro and young gun Kai Allen.

De Silvestro ran full-time in the series earlier in the decade, and Allen is tipped to be a superstar of the future.

The Gen3 issue as well as several other regulation changes mean there are an unusually high number of unknowns going into practice starting on Thursday.

Given that, plus the Mustang's parity woes, Johnson said just finishing the race would mean success.

"Given how bloody competitive this category is, if they finish in the top-10, that would be an absolutely unbelievable result," he said.

Practice for the 60th anniversary of the Great Race begins on Thursday, ahead of the race at 11.15am Sunday.

It's about 10.30am forty years ago – October 1, 1983 in Bathurst, NSW.

Dick Johnson, at the wheel of his iconic Greens-Tuf Palmer Tube Mills No.17 Ford XE Falcon crossed the line to start his lap in the Hardies Heroes – now the top-10 shootout – in a quest for pole for the James Hardie 1000 the next morning.

His Bathurst fortunes had been up and down over the past couple of years. He famously hit a rock rolled onto the track by a fan in 1980, and then brought a brand new car in 1981 and won it.

READ MORE: 'Justin Bieber of league' could make the game millions

READ MORE: The Gould question Freddy can't answer after quitting

READ MORE: Awkward problem caused by Warriors great's return

He finished fourth in 1982 but was disqualified after stewards in post-race scrutineering determined his team had modified the cylinder heads.

Johnson said his team later took a brand new set of cylinder heads to them in an effort to have the decision overturned. They refused.

"We just had to f--king cop it," he told Wide World of Sports a week out from the 2023 edition of the race.

He arrived at the Mountain in '83 with a new co-driver, Kevin Bartlett. They had a fast car, and Johnson felt they would go into the race favourites.

The lap

Johnson did a 2min16.3 seconds to qualify in second place, a second behind who else but Peter Brock.

Back then, the Hardies Heroes was the fastest eight cars and two wildcards, and each driver had the opportunity to do two laps in a final effort to start from pole.

The two wildcards would go out first, and then through the qualifying lineup in reverse order. Rinse and repeat.

Johnson would be ninth to set his lap.

The massive V8 slid through the first turn, called Hell Corner, and straightened up to make the charge up the long, uphill Mountain Straight.

On the exit of The Cutting, the Falcon brushed past the weeds growing out of the earth embankment. There were far fewer concrete walls then.

Through the undulating sections past McPhillamy Park and across Skyline, the car was remarkably settled.

In his book covering the '83 edition of the race, motoring journalist Phil Tuckey recalled watching the lap on a TV screen in the BMW pit.

From somewhere over his shoulder a team member could barely believe the level of commitment on display.

"Holy f--k, he is absolutely off this planet," they said.

Johnson left two massive tyre marks as he got on the power as the car compressed through the Dipper.

He nearly put two wheels in the dirt as he turned in at Forrest's Elbow – the final corner before Conrod Straight.

What happened in the next 10 seconds began one of the most iconic series of events in the history of Australian motorsport.

"It was full on, I was giving it everything I had, and used every inch of the road and some," Johnson said.

"The car was not behaving as well as it should … it had too much understeer, and when I got to Forrest's Elbow, the understeer took me towards the concrete wall."

The first half of the Elbow is positively cambered – that's to say the road slopes towards the inside of the corner. The second half, the opposite. It has negative camber, and the road slopes towards the outside.

As the massive Falcon rounded the corner and the camber-change, understeer became oversteer and the rear-end stepped out.

Johnson said he thought he would give the concrete wall a bit of a kiss, which would straighten the car up, and he would power down Conrod.

But instead, that first impact was heavier than he expected, and it lifted the car into the air slightly. As it settled, the front wheel clipped the concrete-filled tyre bundle that protected the traffic that would travel in the opposite direction for the other 51 weeks of the year from the end of the concrete wall.

It snapped the steering arm, and when the car landed, the wheel turned hard right and fired the car straight into the bush.

Tuckey, who died in 2016, described the crash as "the sort of revenge the mountain waits for all year".

Miraculously, Johnson was alive. The car though, was most definitely not.

To complicate manners, the Falcon carried Channel Seven's world-leading Race Cam which was a far stretch from the lipstick-sized cameras that sit in the cars today.

It was a massive unit – a full-sized television camera mounted to the rollcage, with a box carrying all the other bits and pieces required to run it that weighed about 20kg mounted to the floor.

"Once I went through the trees and the car stopped, I couldn't get out of the driver's side," Johnson said

"I crawled over the camera and I can't remember a thing after that until I (was) walking up the back of the pits with Jilly."

Jilly is his devoted wife Jill. The pair have been married for more than 50 years.

When Johnson slid off the road, he took with him a television cable running along the side of the track. Screens in pit lane went black a split-second after Johnson hit the trees.

It only added to the sense of angst that was sweeping through the paddock. Jill, who usually confined herself to a corner of the pit garage, ran out the back in tears.

If you're wondering why the footage from that onboard has never seen the light of day, a Seven producer forgot to press record before Johnson left the pits.

The legend goes Johnson's co-driver, Kevin Bartlett offered to recreate the crash "for a heap of money".

The conversion

Peter Brock was on his warm-up lap before his own hot lap when he came across the crash scene. He stopped and gave him a lift back to the pits, arriving about 11am.

"And then by midday, we'd done a bit of a deal and that's when the boys got to work," Johnson said.

That "deal" was with fellow competitor Andrew Harris, who had offered to 'donate' – with a lot of money, Johnson added – his Channel Nine-sponsored Falcon to get the No.17 back in the field. The money came from Ross Palmer, of Palmer Tube Mills.

Harris recognised the punters across the top of the mountain would much rather see Johnson in the race than himself. He would later say the idea came to him after Jill ran past him as she left the DJR garage.

Although they were both XE Falcons, Johnson said the two cars were "significantly" different.

While Harris was more or less a privateer running the race on a shoestring budget, Johnson's team was one of the most professional on the grid.

Both Johnson and Bartlett did a couple of slow laps of the circuit that afternoon to make sure the car wasn't a complete death trap. They lapped some 15 seconds slower than their own car, but the deal was done.

The DJR crew got the mangled wreckage of the No.17 back some time in the mid-afternoon and then stripped it of any salvageable running gear.

Work commenced converting No.9 into No.17 about 5pm. It was an all-night job. By the time all Johnson's spares had been bolted on, dawn was approaching, and the car was sent to a crew of 10 apprentice panel beaters, painters and signwriters.

A job that would normally have taken four days, they did in four hours.

To this day, the Bathurst TAFE still plays a vital role in repairing crashed cars over the weekend of the Bathurst 1000, particularly in the support categories.

While changing cars was permitted in the rules, it would usually mean a rear-of-grid start.

In a display of incredible sportsmanship, the rest of the field voted to let Johnson start the race from 10th.

Johnson had earlier joked he planned to use the warm-up lap to dry the paint, but that was the reality. The field had well and truly formed by the time he rolled onto the grid.

But the fresh green paint was still wet – a fact learned the hard way by Seven startline reporter Evan Green, who leaned up against the side of the car, and got paint on his bright red jacket.

Johnson told Wide World of Sports a moment like that is unlikely ever to happen again – the sport is far too professional.

Perhaps the teams let Johnson start 10th because they knew he was no chance to finish.

Indeed, the car expired on lap 61 of the 163-lap journey with a flat battery – a fuse failure meant the alternator wasn't charging it.

The part cost about five cents.

It can't get any worse, can it?

Driving with Larry Perkins, Brock won the race - his seventh of the nine Bathurst titles he would eventually win.

But that wasn't without controversy either - his famous No.05 blew an engine on lap eight, so Brock and Perkins jumped into the sister No.25 car driven by Brock's brother Phil and John Harvey.

Since Harvey had started the race and turned laps in that car, he is listed with Peter and Perkins as the winner of the race.

An example of a royal shafting, Phil is not. That decision was one of a series of events that drove a wedge between the pair.

Harris meanwhile, who was forced to drive a Commodore after another replacement Falcon couldn't be sourced in time, finished 10th.

As part of the deal to use the Harris car, Johnson promised to take the car back to Queensland and respray it, and borrowed Harris' Ford F100 Towmaster to get the car back up there.

The borrowed Harris car was on the Towmaster, which was also towing a trailer carrying the mangled wreck.

More disaster. 40km out of Bathurst, the tow ball broke and the whole rig went off the road.

Johnson was once again unharmed. But the F100, the Harris car and the trailer were all destroyed.

When he eventually got home to Brisbane, his house had also been broken into.

'I'm still bloody here'

Johnson would win the race twice more, in the insane Ford Sierra RS500 in 1989, and then in a Ford EB Falcon as the five-litre formula that went on to become V8 Supercars was in its infancy.

He was driving with John Bowe on both occasions.

DJR ran the Sierras for six seasons during the Group A era. He recalled to Wide World of Sports he nearly claimed a bizarre Bathurst trilogy when he nearly hit a dog across the top.

"I thought to myself, 'jeez, that would've meant I'd hit mineral, vegetable and animal'," he said with a chuckle and all the hallmarks of a tale oft told.

He retired from racing in 1999, handing his iconic No.17 to his son Steven, who raced it until the end of the 2012 season.

These days, Johnson still runs his eponymous team with Ryan Story. The team's base is located in Stapylton, half-way between Brisbane and the Gold Coast.

"I'm still bloody here, working every day," he said.

The team last year became the first ever squad to compete in 1000 races in the Supercars/Australian Touring Car Championship, appropriately at the Bathurst 1000.

He still attends most races, and has no intention of slowing down.

It's been a difficult year for the Ford teams. The introduction of the Gen3 car has brought with it a heavy debate surrounding parity.

Of the 23 races so far, the Chevrolet Camaro has failed to cross the line first only once. Johnson's team is responsible for the only Ford win of the year, through Anton de Pasquale in the Sunday affair in Townsville in June.

Johnson has been a vocal critic of how the sport has handled the parity issue.

Alas, DJR have three cars entered for this year's Great Race.

De Pasquale and Tony D'Alberto will steer the No.11 entry, with brothers Will and Alex Davison in his iconic No.17.

But for Bathurst only, they will also run a third car — a wildcard entry for Swiss superstar Simona De Silvestro and young gun Kai Allen.

De Silvestro ran full-time in the series earlier in the decade, and Allen is tipped to be a superstar of the future.

The Gen3 issue as well as several other regulation changes mean there are an unusually high number of unknowns going into practice starting on Thursday.

Given that, plus the Mustang's parity woes, Johnson said just finishing the race would mean success.

"Given how bloody competitive this category is, if they finish in the top-10, that would be an absolutely unbelievable result," he said.

Practice for the 60th anniversary of the Great Race begins on Thursday, ahead of the race at 11.15am Sunday.

https://ift.tt/T9Gr85y//

No comments:

Post a Comment